Abstract

Recent studies have linked appearance of Paneth cells in colorectal adenomas to adenoma burden and male gender. However, the clinical importance of Paneth cells’ associations with synchronous advanced adenoma (AA) and colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is currently unclear. We performed a comprehensive case-control study using 1,900 colorectal adenomas including 785 from females and 1,115 from males. We prospectively reviewed and recorded Paneth cell status in the colorectal adenomas consecutively collected between February 2014 and June 2015. Multivariable logistic regression analyses revealed that, in contrast to the adenomas without Paneth cells, the Paneth cell-containing adenomas at distal colorectum were inversely associated with presence of a synchronous AA or CRC (odds ratio [OR] 0.39, P = 0.046), whereas no statistical significance was reached for Paneth cell-containing proximal colorectal adenomas (P = 0.33). Synchronous AA and CRC were significantly associated with older age (60 + versus <60 years, OR 1.60, P = 0.002), male gender (OR 1.42, P = 0.021) and a history of AA or CRC (OR 2.31, P < 0.001). However, synchronous CRC was not associated with Paneth cell status, or a history of AA or CRC. Paneth cell presence in the adenomas of distal colorectum may be a negative indicator for synchronous AA and CRC and seems to warrant further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths among both men and women in the United States1. Colonoscopy guidelines recommend that individuals should start having a colonoscopy at the age of 50 years and a potential follow-up colonoscopy depending on the endoscopic findings, particularly the polyp number and characteristics2,3. Certain adenoma characteristics have been associated with an increased CRC risk, including polyp size greater than or equal to 1 cm, villous histology and high-grade dysplasia2,3,4,5,6,7,8. An adenoma with one or more of the 3 characteristics is considered as advanced adenoma (AA, also known as advanced neoplasia) and should be followed up within 3 years, according to the recent update of the U.S. Multi-society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer2. Identification of markers for AA may help with the prevention, early identification and treatment of CRC.

Paneth cells are normally present in the small intestine, proximal colon and transverse colon and contribute to mucosal innate immunity by exerting a number of anti-microbial effects9,10,11. Genetic studies have indicated that Paneth cells upregulate the production of lysozymes, phospholipase A2, the Apc/beta-catenin/Tcf pathway, WNT and CD166, during colonic tumorigenesis11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Paneth cells are also critical for intestinal stem cell homeostasis, as shown by our and others’ works18,19,20. Recently, more attentions have been focused on the role of Paneth cells in CRC development and diagnosis9.

The detection of Paneth cells in colorectal adenomas was reported as early as 196710. The reported frequencies of Paneth cell presence in colorectal adenomas vary significantly, ranging from 0.2 to 39% 15,21,22,23,24. The current consensus view is that Paneth cells are exclusively seen in normal proximal colon (right and transverse colon) and in the injured distal colon and rectum such as the one in inflammatory bowel disease7,21,25,26,27. In terms of the association of Paneth cells with CRC, recent studies reported somewhat contradicting data. One study identifies Paneth cells in the junctional mucosa of 45% of CRC28, while in another study Paneth cell presence was seen in only 2.5% of CRC and 38.5% of conventional adenomas (tubular, villous, or tubulovillous adenomas)15. Paneth cells were also found more frequently seen in CRCs than in tubular adenomas26. Finally, an association was recently reported between Paneth cell containing adenomas and male gender as well as the adenoma burden21. However, it is still not clear whether presence of Paneth cells in colorectal adenomas is associated with presence of synchronous AA or synchronous CRC. This case-control study was specifically designed to address these questions.

Results

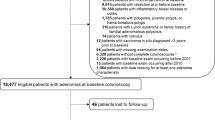

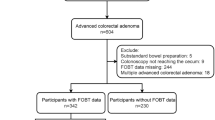

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 3518 cases collected between February 2014 and June 2015 were identified in our study, with 1900 qualified conventional (non-AA) adenomas and AA including 785 from females (17.2% with Paneth cells) and 1115 from males (19.8% with Paneth cells). Compared to the fine, evenly distributed granules and bilobed or trilobed nuclei of eosinophils, Paneth cells show coarse, lumen-facing granules and single round nuclei (Fig. 2A). Overall, 18.7% of the colorectal adenomas showed evidence of Paneth cells, with Fig. 2B as an example.

(A) A tubular adenoma showing many Paneth cells with irregular distribution and coarse eosinophilic granules facing the lumen (200x). The adenomatous cells also show frequent mitoses (left upper corner), unclear hyperchromatia, loss of polarity, crowding/overlapping and pencil-like or round nuclei. (B) A tubular adenoma showing rare eosinophils and no Paneth cells (200x).

Demographic and clinical characteristics pertaining to the presence of Paneth cells in the colorectal adenomas were obtained and reviewed (Table 1). Seventeen hundred and sixty five patients (92.89%) were 50 years of age or older. A history of AA or CRC was significantly associated with Paneth cell absence (P = 0.009) and location of Paneth-cell-containing adenomas (P = 0.029). Table 1 also shows that the adenoma location had a significant association with Paneth cell status (Presence versus absence, P < 0.001).

As Table 2 shows, presence of a synchronous AA or CRC was associated with ages 60 years and older (OR: 1.78, P < 0.001), 65 years and older (OR: 1.58, P < 0.001), male sex (OR: 1.3, P = 0.032) and history of AA or CRC (OR: 2.83, P < 0.001), but not location of adenoma (OR: 0.89, P = 0.072). Paneth cell presence (OR: 0.68, P = 0.054) and Paneth-cell-containing adenoma in the distal colorectum (OR: 0.41, P = 0.057) tended to link to a synchronous AA or CRC. Our multivariable logistic regression analysis (LRA) revealed that Paneth-cell-containing adenoma of the distal colorectum (OR: 0.39, P = 0.046) was inversely associated with a synchronous AA or CRC, in addition to older age (60 + years), male sex and a history of AA or CRC (Table 2). A separate multivariable LRA showed that lack of Paneth cells in adenomas had a trend to link to presence of synchronous AA or CRC (P = 0.054, Table 2).

We then explored the factors potentially associated with synchronous CRC (Table 3). Only history of AA or CRC was found associated with synchronous CRC (OR: 3.47, P = 0.033). Compared with adenomas without Paneth cells, Paneth cell-containing adenomas in the proximal colon (P = 0.157) and in the distal colorectum (P = 0.797) were not associated with synchronous CRC.

Discussion

This case-control study is one of the first studies to investigate the association between Paneth cell presence in colorectal adenomas and synchronous AA and CRC. Our multivariable modeling on the population of conventional adenomas and AA suggested that, compared to the adenomas without Paneth cells, Paneth-cell-containing adenomas at the distal colorectum were inversely (61% likelihood reduction) associated with a synchronous AA or CRC, but not associated with synchronous CRC.

AA is associated with a higher risk of developing CRC and hence warrants a shorter follow-up interval2. Therefore, identification of the factors associated with synchronous AA and CRC may help screen for the patients with a higher likelihood of having an AA and/or CRC. However, despite the important role of Paneth cells in intestinal stem cell homeostasis18,19,20, few studies have investigated the association between synchronous AA/CRC and Paneth cell presence status in colorectal adenomas. Our data seem interesting because they show an inverse relationship between Paneth-cell-containing adenoma at the distal colorectum and presence of a synchronous AA or CRC. The findings are contradictory to the prevailing theories that Paneth cells contribute to the development of colonic epithelial neoplasia through various cellular and molecular mechanisms19,22,29,30. This inverse association provides new and perhaps also important information to the field and raises the question regarding how, if at all, Paneth cells reversely link to the synchronous AA and CRC development in the distal colorectum. Consistent with the findings of this study, our preliminary data of a separate study show a lower frequency of Paneth cell presence in adenomas with villous histology and/or high-grade dysplasia than in conventional adenomas (unpublished data, Xu and Zhang). It is also noteworthy that one of the earlier studies did not reveal any association between Paneth cell presence and the histologic features of AA21.

We did not find any association between race and Paneth cells. This is in contrast to the earlies study showing that Paneth cells are more commonly seen in Japanese descendants and White residents of Hawaii compared to native Japanese23. This discrepancy may be due to our patient population that consisted of 78.4% Whites and 11% Asians. Race also did not have any association with synchronous AA or CRC, despite the earlier finding that African Americans have an increased risk of CRC31. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that only few CRC cases were included in our cohort, along with the predominance of White patients in our study population. The sample size may be too small to reveal a potential association.

Some of this study’s strengths are noteworthy. First, our work appears to fill in the knowledge gap on the association between Paneth cell presence in adenomas and presence of a synchronous AA or CRC. The identified inverse association suggests that Paneth cells in the distal colorectum may be a negative indicator for synchronous AA and CRC. More follow-up studies are needed to confirm our findings. Second, the large-scale of this study seemed to have provided sufficient statistical power in some aspects and may explain the unique factor associated with presence of a synchronous AA or CRC. Indeed, our study also confirms the reported 0.2 to 39% prevalence of Paneth cell presence in colorectal adenomas15,21,22,23,24 and supports the prior findings that Paneth cells were more commonly seen in the proximal colon7,21,25,26,27. Third, case-control studies like ours would be able to dissect the association between the factors and outcomes2,3,32 and may provide a higher level of evidence than case-series studies.

This study had several potential limitations. First, the case-control studies could only examine potential associations, not causality. Therefore, a cohort study is needed to examine whether the presence of Paneth cell in distal colorectum would decrease the risk of synchronous AA and CRC. Second, we used AA as a term combining three characteristics. Separating AA into three distinct categories of high grade dysplasia, size greater than or equal to 1 cm and villous histology could affect the results. Third, none of the potential factors was found associated with presence of a synchronous CRC including some well-known cancer risk factors such as age and adenoma location. One explanation is the small number of the synchronous CRC cases included in our study. In fact, only 16 of our 1900 adenomas had a synchronous CRC (<1%) and none of these cases had presence of Paneth cells. A study with more synchronous CRC cases is needed to validate our findings. Last, we used the data from only one institution and a selection bias may have been resulted in. As discussed earlier, some of the differences between our study and the earlier one21 may be explained by the study population differences. Taken together, caution should be taken while generalizing the findings of this study.

In conclusion, Paneth cell presence in the adenomas at the distal colorectum is inversely associated with presence of a synchronous AA or CRC and may be used as a negative indicator for synchronous AA and CRC. Our findings also suggest an alternative hypothesis that Paneth cells in adenomas of the distal colorectum may link to the suppression of adenoma progression to AA and/or CRC. Future studies are needed to confirm and explain our findings.

Materials and Methods

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro, Plainsboro, New Jersey, USA. The study adheres to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement and was carried out in accordance with the approved IRB protocol and relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Consecutive colorectal polyp cases collected at the University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro, New Jersey between February 2014 and June 2015 were reviewed by a pathologist (LZ) and one of his departmental colleagues and prospectively included in the Princeton Colorectal Polyp Cohort (PCPC) which was started in August 2012. The patients who had an inflammatory bowel disease were excluded from the PCPC. The patient demographics and clinical characteristics obtained for each case consisted of age, sex, self-reported race (White, Hispanic, African American, Asian and others), location of the polyp in the colon, Paneth cell status (started in February 2014), CRC history and polyp history and synchronous colorectal lesions. The inclusion criteria for this case-control study were colorectal adenomas with a known status of Paneth cell presence. Due to the uncertain biological behaviors of sessile serrated polyp/adenoma, it was not included in this study. Both conventional (non-advanced) and AA were included in the study. As prescribed in the recent update of the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer, AA was defined as adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, greater than or equal to 1 cm in size, or with villous histology2. The term of proximal colon included right colon and transverse colon, while distal colorectum included descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum. Therefore, the cutoff point between the proximal colon and distal colonrectum was splenic flexure. The positive history of CRC was defined as a history of CRC given by the caring gastroenterologist or a diagnosis of CRC rendered at our institution three months or more prior to the adenoma-diagnosis time. We used the term synchronous to describe any additional polyps identified during the same endoscopic procedure.

The tissue was processed using standard histological protocols and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. At least 3 levels for each biopsy were examined according to the routine pathology examination protocol in the USA. Presence of one or more Paneth cells is considered as positive for Paneth cells. STATA IC version 11 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for the statistical analyses as described before33. Exact LRA was performed for the variables with no cases (0) in a computation cell/subgroup. If a variable met the criterion of having a P-value of less than or equal to 0.1 as determined by the univariate LRA, it would be included in the multivariable LRA. In the univariate and multivariable analyses, the control group included adenoma cases that did not have synchronous AA or synchronous CRC, while the case group included adenomas with at least one synchronous AA or CRC (Table 2), or with at least one synchronous CRC (Table 3).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mahon, M. et al. Paneth Cell in Adenomas of the Distal Colorectum Is Inversely Associated with Synchronous Advanced Adenoma and Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 6, 26129; doi: 10.1038/srep26129 (2016).

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 65, 5–29, doi: 10.3322/caac.21254 (2015).

Lieberman, D. A. et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 143, 844–857, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001 (2012).

Rex, D. K. et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol 104, 739–750, doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104 (2009).

Lieberman, D. A. et al. Five-year colon surveillance after screening colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 133, 1077–1085, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.006 (2007).

Martinez, M. E. et al. A pooled analysis of advanced colorectal neoplasia diagnoses after colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology 136, 832–841, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.007 (2009).

Martinez, M. E. et al. Adenoma characteristics as risk factors for recurrence of advanced adenomas. Gastroenterology 120, 1077–1083, doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.0050101083 (2001).

Gschwantler, M. et al. High-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas: a multivariate analysis of the impact of adenoma and patient characteristics. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 14, 183–188 (2002).

Bertario, L. et al. Risk of colorectal cancer following colonoscopic polypectomy. Tumori 85, 157–162 (1999).

Clevers, H. C. & Bevins, C. L. Paneth cells: maestros of the small intestinal crypts. Annu Rev Physiol 75, 289–311, doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183744 (2013).

Gibbs, N. M. Incidence and significance of argentaffin and paneth cells in some tumours of the large intestine. J Clin Pathol 20, 826–831 (1967).

Porter, E. M., Bevins, C. L., Ghosh, D. & Ganz, T. The multifaceted Paneth cell. Cell Mol Life Sci 59, 156–170 (2002).

Imai, T. et al. Significance of inflammation-associated regenerative mucosa characterized by Paneth cell metaplasia and beta-catenin accumulation for the onset of colorectal carcinogenesis in rats initiated with 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine. Carcinogenesis 28, 2199–2206, doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm118 (2007).

Ito, M., Suzuki, H., Sagawa, Y. & Homma, S. The identification of a novel Paneth cell-associated antigen in a familial adenomatous polyposis mouse model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 400, 548–553, doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.08.096 (2010).

Feng, Y. et al. Sox9 induction, ectopic Paneth cells and mitotic spindle axis defects in mouse colon adenomatous epithelium arising from conditional biallelic Apc inactivation. Am J Pathol 183, 493–503, doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.013 (2013).

Joo, M., Shahsafaei, A. & Odze, R. D. Paneth cell differentiation in colonic epithelial neoplasms: evidence for the role of the Apc/beta-catenin/Tcf pathway. Hum Pathol 40, 872–880, doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.12.003 (2009).

Levin, T. G. et al. Characterization of the intestinal cancer stem cell marker CD166 in the human and mouse gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology 139, 2072-2082 e2075, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.053 (2010).

Rubio, C. A. Colorectal adenomas produce lysozyme. Anticancer Res 23, 5165–5171 (2003).

Gregorieff, A., Liu, Y., Inanlou, M. R., Khomchuk, Y. & Wrana, J. L. Yap-dependent reprogramming of Lgr5(+) stem cells drives intestinal regeneration and cancer. Nature 526, 715–718, doi: 10.1038/nature15382 (2015).

Das, S. et al. Rab8a vesicles regulate Wnt ligand delivery and Paneth cell maturation at the intestinal stem cell niche. Development 142, 2147–2162, doi: 10.1242/dev.121046 (2015).

Sakamori, R. et al. Cdc42 and Rab8a are critical for intestinal stem cell division, survival and differentiation in mice. J Clin Invest 122, 1052–1065, doi: 10.1172/JCI60282 (2012).

Pai, R. K. et al. Paneth cells in colonic adenomas: association with male sex and adenoma burden. Am J Surg Pathol 37, 98–103, doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318267b02e (2013).

Wada, R., Yamaguchi, T. & Tadokoro, K. Colonic Paneth cell metaplasia is pre-neoplastic condition of colonic cancer or not? J Carcinog 4, 5, doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-4-5 (2005).

Wada, R., Kuwabara, N. & Suda, K. Incidence of Paneth cells in colorectal adenomas of Japanese descendants in Hawaii. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 9, 286–288 (1994).

Bansal, M., Fenoglio, C. M., Robboy, S. J. & King, D. W. Are metaplasias in colorectal adenomas truly metaplasias? Am J Pathol 115, 253–265 (1984).

Wada, R. Proposal of a new hypothesis on the development of colorectal epithelial neoplasia: nonspecific inflammation–colorectal Paneth cell metaplasia–colorectal epithelial neoplasia. Digestion 79 Suppl 1, 9–12, doi: 10.1159/000167860 (2009).

Wada, R. et al. Incidence of Paneth cells in minute tubular adenomas and adenocarcinomas of the large bowel. Acta Pathol Jpn 42, 579–584 (1992).

Mattar, M. et al. Clinicopathologic significance of synchronous and metachronous adenomas in colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 5, 274–278 (2005).

Pai, M. R., Coimbatore, R. V. & Naik, R. Paneth cell metaplasia in colonic adenocarcinoms. Indian J Cancer 35, 38–41 (1998).

Yu, T. et al. Kruppel-like factor 4 regulates intestinal epithelial cell morphology and polarity. PloS one 7, e32492, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032492 (2012).

Salzman, N. H., Underwood, M. A. & Bevins, C. L. Paneth cells, defensins and the commensal microbiota: a hypothesis on intimate interplay at the intestinal mucosa. Semin Immunol 19, 70–83, doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.04.002 (2007).

Chu, K. C., Tarone, R. E., Chow, W. H. & Alexander, G. A. Colorectal cancer trends by race and anatomic subsites, 1975 to 1991. Arch Fam Med 4, 849–856 (1995).

Guyatt, G. H. et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336, 924–926, doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD (2008).

Zhu, H. et al. Histology subtypes and polyp size are associated with synchronous colorectal carcinoma of colorectal serrated polyps: a study of 499 serrated polyps. American journal of cancer research 5, 363–374 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by an Initiative for Multidisciplinary Research Teams (IMRT) award from Rutgers University, Newark, NJ (to N.G. and L.Z.). N.G. is supported by NIH R01DK102934 and ACS Scholar Grant RSG-15-060-01-TBE. We wish to thank the reviewers for their time and insightful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

study concept and design (M.M., J.X., X.Y., X.L., N.G. and L.Z.); acquisition of data (M.M. and L.Z.); analysis and interpretation of data (M.M. and L.Z.); drafting of the manuscript (M.M. and L.Z.); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (M.M., J.X., X.Y., X.L., N.G. and L.Z.); statistical analysis (M.M. and L.Z.); obtained funding; administrative, technical, or material support (N.G. and L.Z.; study supervision (L.Z.).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mahon, M., Xu, J., Yi, X. et al. Paneth Cell in Adenomas of the Distal Colorectum Is Inversely Associated with Synchronous Advanced Adenoma and Carcinoma. Sci Rep 6, 26129 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26129

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26129

This article is cited by

-

Gastroesophageal junction Paneth cell carcinoma with extensive cystic and secretory features – case report and literature review

Diagnostic Pathology (2019)

-

Two-photon microscopy of Paneth cells in the small intestine of live mice

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Inflammation and Colorectal Cancer

Current Colorectal Cancer Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.