Abstract

Deletion of the Casp8 gene in epithelial tissues of mice results in severe inflammatory pathologies. Its ubiquitous deletion, or its specific deletion in endothelial cells, results in intrauterine death associated with capillary damage. These pathologies are all preventable by co-deletion of Casp8 and the genes encoding either the RIPK1 or the RIPK3 protein kinase. Since activation of RIPK3 in Caspase-8-deficient cells can trigger necroptotic cell death, and since RIPK1 can activate RIPK3, it is widely assumed that the inflammatory states resulting from Caspase-8 deficiency occur as a consequence of RIPK3-induced necroptosis. Here, we report that although on a Ripk3-null background Casp8 deletion in mice does not result in outright pathological changes, it triggers enhanced expression of a variety of inflammatory genes in utero, which gradually subsides after birth. Deletion of Ripk1, or even of only one of its two alleles, obliterates this activation. Resembling the embryonic pathology observed in RIPK3-expressing cells, the activation of inflammatory genes observed on a Ripk3-null background seems to be initiated in endothelial cells. Analysis of endothelial cells isolated from livers of Caspase-8-deficient embryos revealed neither an increase in the amount of RIPK1 in these cells after Casp8 deletion, nor triggering of RIPK1 phosphorylation. These findings indicate that the triggering of inflammation by Casp8 deletion in mice occurs, in part, independently of necroptosis or other functions of RIPK3, and rather reflects enhanced RIPK1-dependent signaling for activation of inflammatory genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caspase-8 is unique among members of the caspase cysteine protease family with regard to the far-reaching functional consequences of its deficiency. While its activation triggers apoptotic cell death through the extrinsic cell-death pathway [1, 2], deletion of the Casp8 gene, or that of FADD—the adapter protein to which Caspase-8 binds—results in circulatory failure and death of mice at mid-gestation, associated with damage to capillaries [3,4,5,6]. The same lethal effect in utero is observed when the Casp8 gene is specifically deleted in endothelial cells [7]. On the other hand, its deletion in epithelial tissues such as the epidermis or the intestinal epithelium triggers a severe chronic inflammatory state post-partum, associated with massive tissue damage [8, 9].

The finding that certain pathogens have evolved mechanisms to block the function of caspases, including that of Caspase-8, has drawn considerable attention to mechanisms accounting for the inflammatory states dictated by Casp8 deletion, and the possible real-life corollaries of these experimental pathologies [10]. Assessment of the consequences of Caspase-8 deficiency in cultured cells revealed that these cells, while resistant to apoptotic-death induction by receptors of the TNF family, display dramatically enhanced vulnerability to the induction of necroptotic death [11,12,13]. Since necrotic cell death yields the release of pro-inflammatory cellular components (danger-associated molecular patterns—DAMPs), it is widely assumed that the acute inflammatory pathologies observed when Casp8 is deleted in epithelial tissues, as well as the fatal outcome of its ubiquitous deletion, result from the triggering of necrotic cell death [14]. Supporting this notion was the finding that deletion of the genes encoding either the RIPK1 or the RIPK3 protein kinase, previously shown to participate in signaling for necroptotic death, or of the pseudokinase MLKL which, once phosphorylated by RIPK3, mediates the cellular membrane rupture that triggers this death, attenuates the pathological states inflicted by Caspase-8, or FADD deficiency [13, 15,16,17,18,19].

Here, we analyze the impacts of Casp8, Ripk1, and Ripk3 deletion on the intrauterine expression of inflammatory genes in mice. We show that although the outright pathological changes known to result from Casp8 deletion depend on the function of RIPK3 [3,4,5,6,7,8,9], the expression of some inflammatory genes is enhanced by Casp8 deletion even on a Ripk3-null background. This enhanced expression was found here to be strictly dependent on expression of RIPK1. These findings implicate a mechanism that is independent of RIPK3 or of death induction by it, yet depends on RIPK1, in the inflammatory processes triggered by Caspase-8 deficiency.

Results

Caspase-8 deficiency on a Ripk3-null background triggers upregulation of inflammatory genes in various embryonic tissues

Caspase-8-deficient mice on a Ripk3-null background (Casp8−/−Ripk3−/−) display no evident histological abnormalities in utero [13, 15] (data not shown). However, on examining the livers of these Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− embryos at E16.5 we found, serendipitously, that their expression of the mRNA encoding the inflammatory mediator IL-1β was significantly higher than in age-matched Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− embryonic livers. By employing the Nanostring technique to profile the genes expressed in embryonic livers of those Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− embryos, using a panel of 547 mouse genes known to contribute to the immune response, we found that besides the increase in interleukin Il1b, Caspase-8 deficiency also resulted in upregulation of many other inflammatory genes (Fig. 1a).

Upregulation of inflammatory genes in the embryonic tissues of Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice. a NanoString analysis of the upregulation of immunoregulatory genes in fetal livers of Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice at E16.5. Shown are the relative mRNA expression values in the livers of three Casp8−/−Ripk3−/−and three Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− mice for genes that were upregulated by more than 2-fold (p < 0.05) in the Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− samples. Red color indicates expression levels higher than the average value of the particular gene in the six examined embryonic livers. b Comparison of the effects of Caspase-8 deficiency on levels of the indicated mRNAs in various mouse organs at different embryonic ages (E12.5, E14.5, and E16.5) and at different times after birth (PN1, PN3, PN5, and PN7), and on their overall levels in the embryos at E10.5. Values are expression levels in the indicated organs of Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice (red circles) normalized to those of Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− mice (blue circles), assessed by analyzing at least five embryos or mice from 3 litters. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 relate to differences between the mean values for Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− and Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− mice. c Assessment of the effect of deletion of just one Casp8 allele on the expression of inflammatory genes. Shown is expression of the indicated genes in the livers of Casp8+/+Ripk3−/− and Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− E16.5 mouse embryos (n = 4). No significant differences were found. d Immunoblot analysis of MARCO protein in whole liver extracts from embryos at E16.5. Data are representative of three independent experiments

The expression of four of these genes—Il1b, Ccl5, Cxcl10, and Marco—was then assessed in various tissues at different embryonic stages as well as post-partum. As shown in Fig. 1b, Caspase-8 deficiency resulted in enhanced expression of all four of these genes in embryonic lung, intestine and kidney, as well as in the yolk sac and was discernible, to varying extents, in these tissues as early as E12.5. Analysis of the expression of these genes in whole Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− E10.5 embryos revealed that the expression of Il1b, Cxcl10, and Marco is already increased by that stage. Evidently, therefore, this increase had already occurred before or at the time of the pathological changes inflicted by deletion of Casp8 from RIPK3-expressing embryos, which occurs at about E10.5 [3] (Fig. 1b).

After birth, the basal levels of the examined inflammatory genes were found to increase in the liver and lung, while remaining low in the intestine and kidney (Supplemental Fig. S1). In all four tissues, Caspase-8 deficiency resulted in some further increase in expression of the tested genes, for several days after birth. However, the extent of this increase was significantly lower than that observed before birth (Fig. 1b).

Deletion of just one of the Caspase-8 alleles did not result in increased expression of any of the four examined genes in the embryonic livers (Fig. 1c).

Using antibodies against MARCO for immunoblotting, we found that the amounts of MARCO protein in the livers of E16.5 Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− embryos were much higher than in Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− livers (Fig. 1d). Thus, upregulation of at least part of the inflammatory genes found to be activated in the Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice resulted in enhanced expression of their encoded proteins.

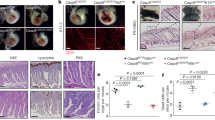

Inflammatory-gene activation due to Caspase-8 deficiency seems to begin preferentially in endothelial cells and then be transmitted to other cells

To identify the liver cell type(s) in which deficiency of Caspase-8 on a Ripk3-null background triggers inflammatory gene expression, we used mice with a “floxed“ Caspase-8 allele (Casp8fl/fl) on a Ripk3-null background to specifically delete Casp8 in each of the main cell types in the liver. Mating of the Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/− mice with mice expressing Cre under control of the albumin promoter allowed deletion of Casp8 specifically in hepatocytes. The use of mice expressing Cre under control of the LysM promoter allowed deletion of Casp8 in the myelomonocytic cells of the liver, and the use of mice expressing Cre under control of the Tie1 promoter allowed its deletion in the endothelial and hematopoietic progenitor cells. The effectiveness of Casp8 deletion by all three Cre transgenes was high (Supplemental Fig. S2). Surprisingly, despite the predisposition of myelomonocytic cells to strongly express inflammatory genes, deletion of Casp8 in these cells did not lead to upregulation of inflammatory genes in the liver. Deletion of Casp8 in hepatocytes (the predominant liver cells) resulted in only mild activation of just two genes. In contrast, deletion of Casp8 by expression of Cre under the Tie1 promoter resulted in strong upregulation of multiple inflammatory genes, and in several of them to an extent similar to that obtained when Casp8 was deleted ubiquitously (Fig. 2a, b).

Cell-type specificity of the upregulation of inflammatory genes in Caspase-8-deficient embryonic liver. a NanoString analysis of the upregulation of immunoregulatory genes in embryonic livers of Ripk3−/− mice at E16.5, as a result of ubiquitous deletions of the Casp8 gene (left-most column; data are from the experiment described in Fig. 1a) or its cell-type-specific deletion by the indicated Cre transgenes. Shown are the averages of the increases in expression of the genes presented in Fig. 1a for three pairs of embryos of the following genotypes: Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− vs. Casp+/−Ripk3−/− from 3 litters; Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/−Alb- Cre vs. Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/− (2 litters); Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/−Tie1-Cre vs. Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/− (1 litter); and Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/−LysM-Cre vs. Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/− (1 litter), compared to those of mouse embryos that did not express the Cre transgenes. #, undetectable. Red color indicates an expression level higher than the average value of the particular gene in the corresponding control samples. b Real-time PCR validation of expression levels of the indicated mRNAs in the livers of the E16.5 mice analyzed in a. Blue circles indicate Casp8fl/fl control samples; red circles indicate tissue-specific Caspase-8-deficient samples. Horizontal lines indicate mean values for each group. The Il1b expression data were obtained by analysis of 10 pairs of Tie1-Cre (4 litters), 6 pairs of Alb-Cre (3 litters), 5 pairs of LysM-Cre mice (2 litters). The data about the expression of Marco, Ccl5, and Cxcl10 were obtained by analysis of three pairs of Tie1-Cre (2 litters), three pairs of Alb-Cre (2 litters), and three pairs of LysM-Cre mice (1 litter). **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 relate to differences between the mean values for the Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/− and Casp8fl/fl Ripk3−/− Cre mice. c Heat-map analysis of the relative mRNA expression, as determined by NanoString analysis, in cells sorted by FACS from three pairs (3 litters) of Casp8+/− Ripk3−/− and Casp8−/− Ripk3−/− fetal liver cells, using antibodies against the indicated cell-surface markers. Data are presented as in a. d Real-time PCR analysis of the cellular levels of mRNAs of Il1b and Marco in the indicated cell populations isolated as in c. Shown are the expression levels in cells derived from Casp8−/− Ripk3−/− (red circles) normalized to those from Casp8+/− Ripk3−/− mice (blue circles). Horizontal lines indicate mean values for each group. Data for Il1b were obtained by analysis of seven pairs (2 litters), and for Marco by analysis of four pairs (2 litter). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 relate to differences between the mean values for the Casp8−/− Ripk3−/− and Casp8+/− Ripk3−/− mice

As an alternative approach to identifying the liver cell type(s) in which Caspase-8 deficiency triggers inflammatory gene expression, we applied antibodies to CD31 (a specific cell-surface marker for endothelial cells) and to CD45 (a cell-surface marker for hematopoietic cells) in order to sort out, by FACS, distinct cell types from the livers of Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− and Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− E16.5 embryos. We then assessed gene expression in the isolated cells. Figure 2c shows that of the three types of cells isolated in this way, only the endothelia (CD45−CD31+ cells) expressed a variety of different inflammatory genes at very high levels. The gene for MARCO, however, was strongly upregulated in all cell types (Fig. 2c, d).

Taken together, the findings reached by both of these modes of analysis indicated that triggering of inflammatory gene expression in the liver on a Ripk3-null background is largely restricted to endothelial cells. Once activated, however, some of these genes are apparently able to upregulate the expression of inflammatory genes in other types of liver cells.

Upregulation of inflammatory genes in Casp8 −/− Ripk3 −/− embryos yields systemic expression of inflammatory mediators

The dissimilar findings obtained by the above two approaches used to identify the cell type in which Caspase-8 deficiency triggers activation of inflammatory genes, as well as the multiplicity of tissues in which such activation was found, suggested that the activation occurs in part in a non-cell-autonomous manner. To define the operative mechanism, we applied ELISA to determine the extent to which inflammatory mediators occur in the sera of the embryos. We found that expression levels of the chemokines CXCL10 and CCL5, the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF and the acute-phase protein SAA3 in the sera of Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− embryos were all increased to a significantly greater extent than in the sera of Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− embryos (Fig. 3a, b). These results are consistent with the observed upregulation of genes encoding soluble pro-inflammatory mediators in the Caspase-8-deficient endothelium (Fig. 2), and may well account for the apparently non-cell-autonomous activation of inflammatory genes in all other cell types in the liver (Fig. 2c, d).

Serum expression of inflammatory mediators in Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice. Serum concentrations of the cytokines CXCL10, CCL5, TNF-α, and the acute-phase protein SAA3 (a, b) in fetal blood of E16.5 embryos and in blood withdrawn postnatally at the indicated ages (c, d). Shown are values of the indicated proteins in plasma samples collected from more than five pairs (from 5 litters) of Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− and Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice, as determined (a, c) by multiplex ELISA and by conventional ELISA (b, d). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 relate to differences between the mean values for the Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− and Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− mice

Some increase in CXCL10, CCL5, and SAA3 was also observed in the sera of Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice during the first week after birth, but had abated by the time the mice were 3 months old (Fig. 3c, d). This increase is thus temporally distinct from the increase in inflammation and in serum cytokines in Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice that is found to occur rather late after birth, as a consequence of a lymphoproliferative syndrome that they develop [13, 15, 19].

The increased expression of inflammatory genes due to Caspase-8 deficiency is dependent on RIPK1

Having shown that Caspase-8 deficiency in mice dictates upregulation of some inflammatory genes independently of RIPK3, we proceeded to examine how this upregulation is affected by deletion of the gene encoding RIPK1. We found that whereas in mice expressing both alleles of Ripk1 the deletion of Casp8 on a Ripk3-null background resulted in marked upregulation of Il1b, Ccl5, Cxcl10, and Marco expression, no such increase was observed in the livers of embryos that were also deficient in RIPK1 or even in only one of the two Ripk1 alleles (Fig. 4a). Nanostring analysis using an immunoregulatory gene panel confirmed that deletion of just one of the two Ripk1 alleles obliterated the upregulation of the inflammatory genes induced by Caspase-8 deficiency (Fig. 4b).

RIPK1-dependence of inflammatory gene upregulation in the embryonic Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− liver. a Real-time PCR analysis of the cellular mRNA levels of the indicated genes in fetal livers of mice with the indicated genotypes at E16.5. Each circle corresponds to the average ratio of gene expression in the livers of embryos with the indicated genotypes to that of Casp8+/−Ripk1+/+ Ripk3−/− embryos, obtained in four independent experiments, as follows: 5 (3 litters) Casp8+/−Ripk1+/+ Ripk3−/− to 4 (3 litters) Casp8−/− Ripk1+/+ Ripk3−/− mice; 1 (1 litter) Casp8+/−Ripk1+/+ Ripk3−/− and 1 (1 litter) Casp8−/− Ripk1+/+ Ripk3−/− mice and 2 (1 litter) Casp8−/− Ripk1+/− Ripk3−/− to 1 (1 litter) Casp8−/− Ripk1−/− Ripk3−/− mice; 3 (2 litters) Casp8−/− Ripk1+/+ Ripk3−/− mice and 5 (3 litters) Casp8−/− Ripk1+/− Ripk3−/− mice to 1 (1 litter) Casp8−/− Ripk1−/− Ripk3−/− mice; 4 (2 litters) Casp8−/− Ripk1+/− Ripk3−/− mice to 2 (2 litters) Casp8−/− Ripk1−/− Ripk3−/− mice. Horizontal lines indicate mean values for each group. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 relate to differences between the mean values for the experimental and control groups of mice. b Nanostring analysis of the effect of Casp8 deletion on the expression of the genes presented in Fig. 1b in mice with two Ripk1 alleles (upper panel: data are from the experiment described in Fig. 1b) or only one 1 Ripk1 allele (lower panel). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 2 (2 litters) Casp8+/−Ripk1+/− Ripk3−/− mice; 3 (3 litters) Casp8−/−Ripk1+/− Ripk3−/− mice; 3 (3 litters) Casp8+/−Ripk1+/+ Ripk3−/− mice; and 3 (3 litters) Casp8−/−Ripk1+/+ Ripk3−/− mice, normalized to the average levels in the corresponding Casp8+/− mice

Caspase-8 deficiency does not cause increased expression of RIPK1 in endothelial cells, nor does it seem to trigger RIPK1 phosphorylation

Caspase-8 has been shown to respond to various stimuli by cleaving RIPK1, thereby arresting its signaling activities [20,21,22]. Given our finding that the upregulation of inflammatory genes in our Caspase-8-deficient embryos is strictly dependent on their adequate expression of RIPK1, it seemed possible that this upregulation reflects cessation of the constitutive downregulation of RIPK1 expression through Caspase-8-mediated RIPK1 cleavage. In such a case, RIPK1 levels in the embryonic endothelial cells, in which the upregulation of inflammatory genes occurs, would be expected to increase. To examine this possibility, we designed a two-step antibody-assisted enrichment protocol to isolate the endothelial cells from embryonic livers at E16.5. As shown in Fig. 5, western analysis using an anti-RIPK1 antibody, enabling us to reliably assess a change in RIPK1 expression resulting from deletion of one of the Ripk1 alleles, revealed no difference between the amounts of RIPK1 in endothelial cells isolated from the livers of Casp8+/−Ripk3−/− and of Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− embryos.

Assessment of the effects of Casp8 deletion on RIPK1 expression and phosphorylation in embryonic endothelial cells. Western blot assessments of the total amounts of RIPK1 and the amounts of RIPK1 phosphorylated at Serine 166 (p-RIPK1), in embryonic livers of mice of the indicated genotypes at E16.5 and in endothelial cells isolated from embryonic livers. Immortalized MEFs, in which RIPK1 phosphorylation was triggered by combined treatment with TNF-α, zVAD and BV6 (TBZ) as described in “Materials and methods”, served as a positive control for detection of p-RIPK1. Albumin and β-actin were blotted as loading controls of the amounts of hepatocyte extracts and for total protein, respectively. Shown are representative results of three independent experiments. NS non-specific band

To this western analysis we then further applied an antibody that specifically recognizes RIPK1 molecules phosphorylated at Serine 166. This antibody allowed easy detection of phosphorylated RIPK1 found in extracts of wild-type mouse fibroblasts that were stimulated by TNF in the presence of a caspase inhibitor and a cIAP antagonist. It did not, however, interact with comparable amounts of RIPK1 found in the Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− embryonic endothelial cells (Fig. 5).

Discussion

The prevailing conception of the various pathological changes resulting from Caspase-8 deficiency is that they are all mediated through a common mechanism in which sequential activation of RIPK1 and RIPK3 results in phosphorylation of the Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like (MLKL) pseudokinase. The latter mediates necroptotic death of Caspase-8-deficient cells, and then DAMPs released by the dying cells trigger the inflammatory changes associated with these various pathologies. Our present findings imply that the inflammatory processes inflicted by Caspase-8 deficiency also involve activation of inflammatory genes by a mechanism that does not depend on the function of RIPK3 or on the death induction by it, but is nevertheless still dependent on RIPK1.

These finding are consistent with the large amount of evidence for contributions of RIPK1 in a variety of ways to the initiation of several signaling pathways that lead to activation of inflammatory genes, including the canonical NF-κB pathway and MAP-kinase cascades. Such participation occurs both in a way that depends on the RIPK1 protein-kinase function and independently of it [23,24,25,26]. Our findings are also consistent with several studies in which Caspase-8 deficiency was found to facilitate such pro-inflammatory functions of RIPK1 without leading to cell death [27,28,29,30].

As expected from the fact that Capase-8 deficiency in RIPK3-deficient embryos does not result in outright pathological changes, the extent of upregulation of inflammatory genes observed in these embryos was far lower than that observed after Casp8 deletion in mice that do express this protein kinase. The marked increase in inflammation seen in the RIPK3-expressing mice might result in part from the initiation of necroptosis. However, in view of growing evidence that RIPK3 can also facilitate inflammation in ways that do not depend on cell death [26, 30,31,32,33], as well as some evidence for death-independent pro-inflammatory functions of the RIPK3 target protein MLKL [34,35,36], it seems likely that part of this enhanced inflammation does not result from necroptotic death but rather reflects non-deadly pro-inflammatory functions of RIPK3 and MLKL.

Our findings suggest that both the increase in expression of inflammatory proteins in RIPK3-deficient mouse embryos and the fatal outcome of Caspase-8 deficiency in embryos that do express RIPK3 are initiated in the same type of cell, namely, the endothelial cells. That finding, together with the similar timing of those changes, raises the possibility that despite marked differences in their consequences, the two mechanisms are interlinked. There are several possible links between the two. One intriguing possibility is that the RIPK3-independent activation of genes in response to deficiency of Caspase-8 is a precondition for those RIPK3-dependent pathologies that develop spontaneously in response to Caspase-8 deficiency. A plausible example of such interdependence is provided by our finding that TNF is one of the genes upregulated by Caspase-8 deficiency on a Ripk3-null background. TNF expression is a precondition for triggering of the RIPK3-dependent damage in E10.5 mouse embryos [37]. It is thus reasonable to hypothesize that the RIPK3-independent generation of TNF in embryos in response to Caspase-8 deficiency is the trigger for the RIPK3-dependent effects. The spontaneous development of pathological RIPK3-dependent consequences of Caspase-8 deficiency in adult mice may likewise depend on prior RIPK3-independent upregulation of some inflammatory genes.

An alternative possible cause of the apparent temporal and spatial co-occurrence of RIPK3-dependent and RIPK3-independent consequences of Caspase-8 deficiency in embryos is the existence of a mechanistic step that is common to both sets of consequences. This possibility raises the need to reconsider the identity of the Caspase-8 molecular target that accounts for the pro-inflammatory effect of deficiency in this caspase. In prior discussions, it was suggested that this consequence of Caspase-8 deficiency reflects the arrest of Caspase-8-mediated cleavage of one or more of three signaling proteins: RIPK1, RIPK3, and the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD [13, 21, 38]. Our finding that Caspase-8 deficiency results in activation of pro-inflammatory genes even in the absence of RIPK3 clearly rules out an exclusive role for arrest of RIPK3-cleavage in this process. The contribution of CYLD to signaling mediated by RIPK1 + RIPK3 occurs through strengthened association of these two proteins and has to do with enhancement of their kinase function [39]. Our observation that inflammatory proteins became activated in the absence of RIPK3 and apparently without phosphorylation of RIPK1 casts doubt on the possibility that CYLD cleavage is a player in the regulation of this process.

Finally, our finding that endothelial cells isolated from Caspase-8-deficient mice and from mice not lacking Caspase-8 contain equal amounts of RIPK1 casts doubt on the arrest of Caspase-8-mediated RIPK1 cleavage as a possible player in this eventuality. In fact, we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed upregulation of inflammatory genes as a result of Caspase-8 deficiency does not reflect the prevention of cleavage of any substrate of this protease, but rather reflects the arrest of some non-enzymatic function of Caspase-8. It has indeed been shown that Caspase-8, besides acting as a protease, also contributes to signaling by serving as a scaffold for the assembly of other signaling proteins [36, 40,41,42].

The cellular expression of RIPK3 is subject to modulation by inducing agents and is increased in various inflammatory diseases [43,44,45]. Our finding that the initiation of inflammation in vivo as a consequence of Caspase-8 deficiency also occurs in the absence of RIPK3, albeit to a much lower degree than in the presence of RIPK3, implies that our cells possess the ability to respond in mild or alternatively in intense manner to pathogens that block caspase action. Such a graded response would offer more discriminatory assistance in overcoming infection. Restraining the expression of RIPK3, or of proteins acting downstream of it, can allow Caspase-8-deficient cells to initiate a defensive response through inflammatory changes not associated with their own damage. Should more powerful means of defense become necessary, upregulation of the expression of RIPK3 and of proteins downstream of it would allow these defense mechanisms to be supplemented by others that do lead to self-destruction of cells and tissues.

Materials and methods

Mice

All mice used in this study were on a C57BL/6 background. Mouse strains carrying a knocked-out Casp8 allele (Casp8−/+) [3] and a conditional Casp8 allele (Casp8 fl/+) [7] were established in our laboratory. The use of mice expressing Cre under control of the albumin promoter (Alb-Cre) [46], the lysozyme M gene promoter (LysM-Cre) [47], and the Tie1 promoter (Tie1−Cre) [48] for deletion of the Casp8 gene specifically in hepatocytes, in liver myelomonocytic cells, and in both endothelial cells and hematopoietic progenitor cells, respectively, has been described [7]. Mice deficient in Ripk1 were obtained from Dr. Michelle Kelliher [49] and mice deficient in Ripk3 from Dr. Vishva Dixit [50]. Embryos and yolk sacs were isolated on the indicated days of timed pregnancies and genotyped by PCR using tail genomic DNA, as described [7]. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at The Weizmann Institute of Science.

FACS sorting

Fetal livers were dissected and incubated in RPMI medium containing collagenase D (50 U/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 5% fetal bovine serum for 40 min at 37 °C. Collagenase-treated tissues were dissociated into single cells by pipetting and filtering through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Red blood cells were removed by treatment with a buffered ammonium chloride solution and then with mouse BD Fc BlockTM (BD Biosciences) for 5 min.

For the experiment presented in Fig. 2c and d, the cells were stained with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-mCD45 antibody (17-0451, BD Biosciences) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mCD31 antibody (11-0311, BD Biosciences), allowing sorting for endothelial cells (CD45−CD31+), hematopoietic cells (CD45+CD31−), and other liver cells (CD45−CD31−).

The effectiveness of Casp8 deletion in individual cell types (Supplemental Fig. S2) was assessed by isolation of endothelial cells by FACS sorting after staining as above, and isolation of macrophages after staining with APC-conjugated anti-F4/80 antibody (17-4801, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody (12-0415, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

For the experiment presented in Fig. 5, endothelial cells from the dissociated fetal liver tissue were isolated using a MACS Cell Separation LS column (Miltenyi Biotech), using anti-CD31 antibody (BD Pharmingen) and anti-rat IgG MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech). They were then further enriched by FACS sorting using anti-CD31 antibody as described above. After sorting, purity testing confirmed that more than 96% of the isolated cells were endothelial.

In all cases, staining with antibodies was carried out for 20 min on ice. The cells were then washed with cold FACS buffer (2% FBS, 0.01% sodium azide) and resuspended in the same buffer for cell sorting using a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences). Immediately before FACS analysis, the DNA dye 7-amino-actinomycin D was added for staining of dead cells. The isolated cells were harvested by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and were either frozen immediately and kept at −80 °C pending extraction of total RNA or genomic DNA, or extracted with detergent for western blot analysis.

Assessing the extent of deletion of the floxed Casp8 allele

The extent of deletion of floxed Casp8 alleles in tissues and cells isolated from mice that express Cre under control of various promoters was assessed by real-time PCR, using DNA extracted with a QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The assay was performed in a total reaction volume of 20 μl containing 30 ng DNA, 300 nM oligonucleotide primers, 100 nM oligonucleotide 3′-Minor groove binder (MGB) probes, and 10 μl of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The PCR procedure was done by subjecting the reaction mixture to incubation for 10 min at 95 °C, and then to 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and of 1 min at 60 °C on an ABI Prism 7300 System (Applied Biosystems). Primers and probes were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). The oligonucleotide primers and probes used to hybridize the floxed region in the Casp8 gene were 5′-TCCTGTGCTTGGACTACATCC-3′ (sense), 5′-TTCCCGCAGCCTCAGAAATAG-3′ (antisense), and 5′-6-FAM- AGAAGCAGGAGACCATCGAGGATGC-MGB-3′ (probe). Data were normalized on the basis of quantification of the non-loxP-flanked region (Exon8) in the Casp8 gene using 5′- GCGCAGACCACAAGAACAAAG-3′ (sense), 5′-CCTTCCCATCCGTTCCATAGAC-3′ (antisense), and 5′-6-FAM-TGCTTCATCTGCTGTATCCTATCCCA-MGB-3′ (probe). The comparative threshold cycle method (ΔCT) was used to quantify the deletion of Casp8.

RNA extraction from tissues or sorted cells

Embryos were dissected on the indicated embryonic day and their organs were isolated and placed in RNAlater Stabilization Solution (Ambion) until processed for RNA extraction. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA from FACS-sorted cells was extracted using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). The quality of the RNA was assessed on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA from tissue or cells was reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript II First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed using the following TaqMan primers and probe sets (Applied Biosystems).

Target gene | Catalog number |

|---|---|

Il1b | Mm00434228_m1 |

Cxcl10 | Mm00445235_m1 |

Ccl5 | Mm01302428_m1 |

Marco | Mm00440265_m1 |

RNA expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene Hprt1 and calculated using the ddCt algorithm.

Profiling of gene expression

NanoString technology with nCounter Digital Analyzer and nSolver software (NanoString Technologies) was used to assess gene expression in the indicated cell types and tissue. Briefly, RNAs were hybridized with the nCounter Mouse Immunology Panel (GXA-MIM1-12) and data were analyzed according to the recommendations of NanoString Technology. Total RNA (100 ng) isolated from fetal liver and from FACS-sorted hematopoietic cells (CD45+ CD31−), or total cell lysates of 6000 sorted endothelial cells (CD45− CD31+) and of the other fetal liver cells (CD45− CD31−) in 1.5 μl of buffer RLT (Qiagen), were hybridized with capture and reporter probes.

Chemokine and cytokine assays in the blood of embryonic and adult mice

Blood samples were collected from the umbilical cords of mouse embryos and from the orbital sinuses of adult mice were collected into EDTA-coated tubes and spun at 1500 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Plasma concentrations of CXCL10, CCL5, and TNF-α were measured using the Magnetic Luminex Screening Assay system (R&D Systems) and a MAGPIX system (Luminex). Plasma concentrations of serum amyloid A3 were determined by ELISA (Merck Millipore), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Stimulation of RIPK1 phosphorylation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)

MEFs immortalized by expression of the SV40 large T antigen were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. RIPK1 phosphorylation was stimulated in the MEFs by their treatment for 3 h with TNF (1000 U/ml), together with the bivalent IAP (inhibitor of apoptosis protein) antagonist BV6 [51] and the caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk (both from WuXi AppTec) at concentrations of 1 and 20 μM, respectively.

Immunoblotting

For the experiment presented in Fig. 1d, whole liver extracts were prepared by boiling fetal liver in 1% SDS-lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS) followed by ultrasonication for 10 s. For the experiment shown in Fig. 5, whole liver extracts, extracts of FACS-purified endothelial cells, and extracts of MEFs were prepared in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% TritonX-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma). Protein concentration in the extracts was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The protein-loaded membrane was blocked with 10% milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, and incubated overnight with the primary antibody and then for 1 h with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Binding of the latter was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-MARCO (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-68623), anti-phospho-RIPK1 (Serine 166; rodent specific) (Cell Signaling Biotech, 31122), anti-RIPK1 (BD Bioscience, 610459), anti-albumin (Cell Signaling Biotech, 4929), and anti-β-actin (Sigma, A5541).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software) Differences between two groups were evaluated by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test and differences among more than two groups were evaluated by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey’s post hoc test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

References

Boldin MP, Goncharov TM, Goltsev YV, Wallach D. Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT1/FADD-interacting protease, in Fas/APO1- and TNF receptor-induced cell death. Cell. 1996;85:803–15.

Muzio M, Chinnaiyan AM, Kischkel FC, O’Rourke K, Shevchenko A, Ni J, et al. FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95 (Fas/APO-1) death-inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996;85:817–27.

Varfolomeev EE, Schuchmann M, Luria V, Chiannilkulchai N, Beckmann JS, Mett IL, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse Caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity. 1998;9:267–76.

Zhang J, Cado D, Chen A, Kabra NH, Winoto A. Fas-mediated apoptosis and activation-induced T-cell proliferation are defective in mice lacking FADD/Mort1. Nature. 1998;392:296–300.

Yeh WC, Pompa JL, McCurrach ME, Shu HB, Elia AJ, Shahinian A, et al. FADD: essential for embryo development and signaling from some, but not all, inducers of apoptosis. Science. 1998;279:1954–8.

Sakamaki K, Inoue T, Asano M, Sudo K, Kazama H, Sakagami J, et al. Ex vivo whole-embryo culture of caspase-8-deficient embryos normalize their aberrant phenotypes in the developing neural tube and heart. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1196–206.

Kang TB, Ben-Moshe T, Varfolomeev EE, Pewzner-Jung Y, Yogev N, Jurewicz A, et al. Caspase-8 serves both apoptotic and nonapoptotic roles. J Immunol. 2004;173:2976–84.

Kovalenko A, Kim JC, Kang TB, Rajput A, Bogdanov K, Dittrich-Breiholz O, et al. Caspase-8 deficiency in epidermal keratinocytes triggers an inflammatory skin disease. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2161–77.

Gunther C, Martini E, Wittkopf N, Amann K, Weigmann B, Neumann H, et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-alpha-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature. 2011;477:335–9.

Mocarski ES, Guo H, Kaiser WJ. Necroptosis: the Trojan horse in cell autonomous antiviral host defense. Virology. 2015;479-480:160–6.

Vercammen D, Beyaert R, Denecker G, Goossens V, Van Loo G, Declercq W, et al. Inhibition of caspases increases the sensitivity of L929 cells to necrosis mediated by tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1477–85.

Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, Thome M, Attinger A, Valitutti S, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:489–95.

Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, McCormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Pop C, et al. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 2011;471:363–7.

Wallach D, Kang TB, Dillon CP, Green DR. Programmed necrosis in inflammation: toward identification of the effector molecules. Science. 2016;352:aaf2154.

Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Daley-Bauer LP, Hakem R, et al. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;471:368–72.

Zhang H, Zhou X, McQuade T, Li J, Chan FK, Zhang J. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature. 2011;471:373–6.

Dillon CP, Oberst A, Weinlich R, Janke LJ, Kang TB, Ben-Moshe T, et al. Survival function of the FADD-CASPASE-8-cFLIP(L) complex. Cell Rep. 2012;1:401–7.

Pasparakis M, Vandenabeele P. Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature. 2015;517:311–20.

Alvarez-Diaz S, Dillon CP, Lalaoui N, Tanzer MC, Rodriguez DA, Lin A, et al. The pseudokinase MLKL and the kinase RIPK3 have distinct roles in autoimmune disease caused by loss of death-receptor-induced apoptosis. Immunity. 2016;45:513–26.

Lin Y, Devin A, Rodriguez Y, Liu ZG. Cleavage of the death domain kinase RIP by caspase-8 prompts TNF-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2514–26.

O’Donnell MA, Perez-Jimenez E, Oberst A, Ng A, Massoumi R, Xavier R, et al. Caspase 8 inhibits programmed necrosis by processing CYLD. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1437–42.

Rajput A, Kovalenko A, Bogdanov K, Yang SH, Kang TB, Kim JC, et al. RIG-I RNA helicase activation of IRF3 transcription factor is negatively regulated by Caspase-8-mediated cleavage of the RIP1 protein. Immunity. 2011;34:340–51.

Festjens N, Vanden Berghe T, Cornelis S, Vandenabeele P. RIP1, a kinase on the crossroads of a cell’s decision to live or die. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:400–10.

Wajant H, Scheurich P. TNFR1-induced activation of the classical NF-kappaB pathway. FEBS J. 2011;278:862–76.

Lukens JR, Vogel P, Johnson GR, Kelliher MA, Iwakura Y, Lamkanfi M, et al. RIP1-driven autoinflammation targets IL-1alpha independently of inflammasomes and RIP3. Nature. 2013;498:224–7.

Moriwaki K, Chan FK. Necroptosis-independent signaling by the RIP kinases in inflammation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2325–34.

Christofferson DE, Li Y, Hitomi J, Zhou W, Upperman C, Zhu H, et al. A novel role for RIP1 kinase in mediating TNFalpha production. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e320.

Cuda CM, Misharin AV, Gierut AK, Saber R, Haines GK 3rd, Hutcheson J, et al. Caspase-8 acts as a molecular rheostat to limit RIPK1- and MyD88-mediated dendritic cell activation. J Immunol. 2014;192:5548–60.

Yatim N, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Orozco S, Schulz O, Barreira da Silva R, Reis e Sousa C, et al. RIPK1 and NF-kappaB signaling in dying cells determines cross-priming of CD8(+) T cells. Science. 2015;350:328–34.

Najjar M, Saleh D, Zelic M, Nogusa S, Shah S, Tai A, et al. RIPK1 and RIPK3 kinases promote cell-death-independent inflammation by Toll-like receptor 4. Immunity. 2016;45:46–59.

Lawlor KE, Khan N, Mildenhall A, Gerlic M, Croker BA, D’Cruz AA, et al. RIPK3 promotes cell death and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the absence of MLKL. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6282.

Newton K, Dugger DL, Maltzman A, Greve JM, Hedehus M, Martin-McNulty B, et al. RIPK3 deficiency or catalytically inactive RIPK1 provides greater benefit than MLKL deficiency in mouse models of inflammation and tissue injury. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1565–76.

Daniels BP, Snyder AG, Olsen TM, Orozco S, Oguin TH 3rd, Tait SWG, et al. RIPK3 restricts viral pathogenesis via cell death-independent neuroinflammation. Cell. 2017;169:301–13 e11.

Kang TB, Yang SH, Toth B, Kovalenko A, Wallach D. Caspase-8 blocks kinase RIPK3-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity. 2013;38:27–40.

Gurung P, Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Vande Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Dillon CP, et al. FADD and caspase-8 mediate priming and activation of the canonical and noncanonical Nlrp3 inflammasomes. J Immunol. 2014;192:1835–46.

Kang S, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Rogers C, Mayes L, Wang Y, Dillon C, et al. Caspase-8 scaffolding function and MLKL regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation downstream of TLR3. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7515.

Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Rodriguez DA, Cripps JG, Quarato G, Gurung P, et al. RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell. 2014;157:1189–202.

Feltham R, Vince JE, Lawlor KE. Caspase-8: not so silently deadly. Clin Transl Immunol. 2017;6:e124.

Moquin DM, McQuade T, Chan FK. CYLD deubiquitinates RIP1 in the TNFalpha-induced necrosome to facilitate kinase activation and programmed necrosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e76841.

Imamura R, Konaka K, Matsumoto N, Hasegawa M, Fukui M, Mukaida N, et al. Fas ligand induces cell-autonomous NF-kappaB activation and interleukin-8 production by a mechanism distinct from that of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46415–23.

Horn S, Hughes MA, Schilling R, Sticht C, Tenev T, Ploesser M, et al. Caspase-10 negatively regulates Caspase-8-mediated cell death, switching the response to CD95L in favor of NF-kappaB activation and cell survival. Cell Rep. 2017;19:785–97.

Henry CM, Martin SJ. Caspase-8 acts in a non-enzymatic role as a scaffold for assembly of a pro-inflammatory “FADDosome” complex upon TRAIL stimulation. Mol Cell. 2017;65:715+.

Zhou W, Yuan J. Necroptosis in health and diseases. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;35:14–23.

Kim SK, Kim WJ, Yoon JH, Ji JH, Morgan MJ, Cho H, et al. Upregulated RIP3 expression potentiates MLKL phosphorylation-mediated programmed necrosis in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2021–30.

Yang C, Li J, Yu L, Zhang Z, Xu F, Jiang L, et al. Regulation of RIP3 by the transcription factor Sp1 and the epigenetic regulator UHRF1 modulates cancer cell necroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e3084.

Kellendonk C, Opherk C, Anlag K, Schutz G, Tronche F. Hepatocyte-specific expression of Cre recombinase. Genesis. 2000;26:151–3.

Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Forster I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 1999;8:265–77.

Gustafsson E, Brakebusch C, Hietanen K, Fassler R. Tie-1-directed expression of Cre recombinase in endothelial cells of embryoid bodies and transgenic mice. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:671–6.

Kelliher MA, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger BZ, Leder P. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303.

Newton K, Sun X, Dixit VM. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1464–9.

Varfolomeev E, Blankenship JW, Wayson SM, Fedorova AV, Kayagaki N, Garg P, et al. IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-kappaB activation, and TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007;131:669–81.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tatiana Shalevich for maintaining the cultured cells, Drs. Ron Rotkopf and Ester Feldmesser for assistance with statistical analysis, and both Inna Kolesnik and Shoshana Grossfeld for genotyping the mice. We are grateful to Dr. Irmgard Förster for donating the LysM-Cre mice, Dr. Erika Gustafsson for the Tie1-Cre mice, Dr. Michelle Kelliher for the Ripk1−/− mice, and Dr. Vishva Dixit for the Ripk3−/− mice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Edited by A. Ashkenazi.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, TB., Jeong, JS., Yang, SH. et al. Caspase-8 deficiency in mouse embryos triggers chronic RIPK1-dependent activation of inflammatory genes, independently of RIPK3. Cell Death Differ 25, 1107–1117 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-018-0104-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-018-0104-9

This article is cited by

-

Apoptotic cell death in disease—Current understanding of the NCCD 2023

Cell Death & Differentiation (2023)

-

Ubiquitin-binding domain in ABIN1 is critical for regulating cell death and inflammation during development

Cell Death & Differentiation (2022)

-

The resurrection of RIP kinase 1 as an early cell death checkpoint regulator—a potential target for therapy in the necroptosis era

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2022)

-

Contribution of cell death signaling to blood vessel formation

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2021)

-

Pleiotropic, non-cell death-associated effects of inhibitors of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 in the heart

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2021)