Abstract

Hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72 are the most common cause of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) (c9ALS/FTD). Unconventional translation of these repeats produces dipeptide repeat proteins (DPRs) that may cause neurodegeneration. We performed a modifier screen in Drosophila and discovered a critical role for importins and exportins, Ran-GTP cycle regulators, nuclear pore components and arginine methylases in mediating DPR toxicity. These findings provide evidence for an important role for nucleocytoplasmic transport in the pathogenic mechanism of c9ALS/FTD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions are the most common genetic cause of ALS and FTD (c9ALS/FTD)1,2. Despite the importance of these mutations, the underlying pathogenic mechanisms remain elusive. Three main hypotheses have been proposed to explain how C9orf72 mutations could cause disease: haploinsufficiency due to lowered transcription of the C9orf72 gene, RNA toxicity resulting from the sequestration of essential RNA-binding proteins by sense and antisense repeat RNA foci that accumulate in the nucleus and cytoplasm and repeat associated non-ATG (RAN) translation of sense and antisense RNA3. This unconventional form of translation results in the generation of distinct aggregation-prone dipeptide repeat proteins (DPRs). These DPRs are found in the hallmark p62-positive, TDP-43 negative inclusions seen in c9FTD/ALS patients4,5,6. Mounting evidence points to a direct role of these DPRs in neurodegeneration7,8,9,10 but the mechanism by which these DPRs cause toxicity remains unresolved and of intense interest. Defining the cellular mechanisms of DPR toxicity is necessary to understand the disease pathogenesis and may reveal new targets for therapeutic intervention.

We used Drosophila to investigate the mechanisms by which C9orf72 DPRs cause toxicity and neurodegeneration. To focus specifically on DPR toxicity, we had to experimentally separate the generation of the DPRs from the presence of repeat RNA. We generated expression constructs allowing ATG-mediated expression of a single DPR and codon-optimized these constructs to reduce the formation of stable repeat RNA secondary structures. Hence, these constructs allow us to attribute observed phenotypes solely to expression of one DPR and rule out any confounding RNA toxicity or RAN translation. We generated fly lines expressing 50 repeats of four of the five possible DPRs (GA, GR, PA and PR). Consistent with recent reports8,9,10, we found that expression of the arginine-rich DPRs, GR and PR, strongly reduced survival in flies expressing these DPRs in adult flies either ubiquitously or motor neuron-specific (Fig. S1). Thus, this Drosophila model recapitulates robust C9orf72 DPR toxicity, providing a tractable system to identify and characterize toxicity modifier genes.

Jovičić et al. reported results from two unbiased genome wide screens in yeast for suppressors and enhancers of PR toxicity11. These two screens identified a striking number of modifier genes involved in nucleocytoplasmic transport. These modifiers include karyopherins, nuclear pore complex components and enzymes involved in generating the Ran-GTP gradient that drives nuclear transport. Since the general principles and key molecules of nucleocytoplasmic transport are highly-conserved from yeast to flies to humans12, we sought to validate these results in an animal model and to test the hypothesis that genes involved in nuclear transport could also modify C9orf72 DPR toxicity in vivo. We therefore performed a targeted RNAi screen in Drosophila. To facilitate the rapid identification of modifiers of DPR toxicity, we used eye degeneration as a readout. We directed expression of a single copy of the 25 PR repeat construct to the fly eye. This caused a moderate degenerative phenotype (Fig. 1a), providing the ability to identify both suppressors and enhancers.

Genes implicated in nuclear transport are potent modifiers of PR toxicity in Drosophila.

(a) Expression of a PR25 construct in the fly eye induces a moderate degenerative eye phenotype compared to the eyes of non-affected PA-expressing flies or severely affected flies expressing two copies of the PR25 transgene. (b) Setup of RNAi screen for PR25 modifiers. (c) Knockdown of four karyopherins (Trn, Fs(2)Ket, Kap-alpha3 and Ranbp11) strongly enhanced PR toxicity. (d) Knockdown of RanGTP cycle regulators Rangap and Rcc1 both enhance eye degeneration. (e) Knockdown of some nuclear pore complex components (Nup50, Nup107 and Nup154) suppressed degeneration others (Nup44A, Nup62, Nup93-1) enhanced the phenotype. (a,e) show males, (c,d) females.

To focus on nucleocytoplasmic transport and related processes, we compiled a library of 121 independent RNAi lines targeting 55 fly genes (Table S1), encoding nuclear pore complex proteins, importins, exportins, regulators of the Ran-GTP cycle and arginine methylases, which affect protein localization by modulating NLS sequences13. We expressed each RNAi together with the PR25 construct and scored for the ability to enhance or suppress the phenotype (Fig. 1b, Fig. S2). We identified 15 enhancers and 4 suppressors of the PR25 eye phenotype (Table 1, Table S4). Importantly, the RNAi lines did not cause a degenerative eye phenotype in a wild type background (Fig. S3a) and the RNAi lines that suppressed PR toxicity did not affect PR expression (Fig. S3b).

Knockdown of four members of the importin family (Ranbp11, Kap-alpha3, Fs(2)Ket and Trn), which mediate nuclear import of cargo proteins, caused striking enhancement of the PR25 eye phenotype (Fig. 1c). Knockdown of another importin, CG32165, mildly suppressed toxicity and knockdown of the exportin emb enhanced PR toxicity. We also identified the two regulators of the Ran-GTP cycle (Rcc1 and RanGap) as modifiers of PR25 toxicity (Fig. 1d). Subunits of the nuclear pore complex were suppressors (Nup50, Nup107 and Nup154) and enhancers (Mtor, Nup44A, Nup62 and Nup93-1) (Fig. 1e). Finally, knockdown of four different arginine methyltransferases (Art1, Art6, Art7 and Fbx011) enhanced PR toxicity.

The strongest enhancer of PR-mediated neurodegeneration was knockdown of Trn (Fig. 2a, Fig. S4), the fly ortholog of TNPO1, encoding transportin 1. Of notice, the yeast TNPO1 homolog Kap104 was one of the strongest suppressors of PR toxicity in yeast11. Interestingly, transportin 1 has been connected to another form of ALS/FTD, namely related to FUS13,14. ALS-causing mutations in FUS/TLS impair transportin-mediated nuclear import, resulting in FUS cytoplasmic accumulation and aggregation15 and in FTD cases with FUS pathology transportin 1 is mislocalized to cytoplasmic FUS aggregates14. To determine whether PR could directly act on transportin 1 function, we performed computational docking simulations (Fig. 2b) and predicted that PR can interact with transportin 1. This suggested that PR might compete for endogenous transportin 1 cargoes. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the effect of PR expression on the localization of a well-characterized transportin 1 cargo, the neuronal RNA-binding protein Elav. We observed increased cytoplasmic localization and decreased nuclear staining of Elav in flies expressing PR (Fig. 2c). Moreover, Elav mislocalization increased further upon Trn knockdown (Fig. 2c). Consistent with previous reports, we also observed the cytoplasmic aggregation of the transportin 1 cargo hnRNPA3 in human c9FTD (Fig. 2d, Table S2). These findings suggest a potential role of transportin 1 in the pathogenesis of c9ALS/FTD.

Transportin-1 and arginine methylation are directly implicated in DPR models and C9 patients.

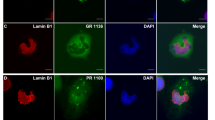

(a) Trn knockdown potently enhanced the PR-induced degenerative eye phenotype. Females are shown. (b) Computational conformational docking predictions predict that PR can fit the transportin-1 binding pocket. Positive arginine side chains of PR (red) interact with the negative side chains (blue) of the binding pocket. (c) Elav is mislocalized to the cytoplasm in PR expressing flies. Mislocalization is exacerbated upon Trn RNAi knockdown. Arrowheads indicate cytoplasmic staining. Scale bar indicates 5 μm. (d) hnRNPA3 is mislocalized in c9FTD cases (arrowheads) but not in disease-negative controls. Picture shows dentate gyrus. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. (e) Art1 knockdown enhances the PR-induced eye phenotype. Males are shown. (f) PR colocalizes with PRMT1 upon cotransfection in HeLa cells, as determined by super resolution microscopy (SIM). (g) GR staining associates with (arrowheads) and partially colocalizes with (arrow) ASYM24 staining in transfected neuroblastoma cells, as determined by SIM. Scale bars indicate 10 μm. (h) Immunostaining with ASYM24 detects methylated pathological aggregates (arrowheads) in dentate gyrus of c9FTD patient samples but not in controls. Scale bar indicates 10 μm.

Finally, knockdown of four out of ten arginine methyltransferase genes enhanced PR toxicity in Drosophila (Table 1, Fig. 2e). One of these, PRMT1, has been previously implicated in ALS caused by FUS/TLS mutations13,16. To determine whether this enzyme could directly affect DPR toxicity, we performed colocalization experiments in cell lines. PRMT1 colocalized with both GR and PR (Fig. 2f, Fig. S5). We subsequently tested several commercially available antibodies to detect methylation. One of them, ASYM24, was able to detect asymmetric arginine dimethylation of GR, but not PR. This was not surprising since this antibody was originally raised against a peptide showing strong sequence similarity with GR, but not PR (Fig. S5). Using this antibody we found GR accumulations to be methylated in transfected cells, but also an association of GR with other methylated proteins, as determined by super resolution microscopy (Fig. 2g). To validate this new aspect of DPR pathology in humans, we performed immunostaining on c9FTD brain samples and detected abundant methylated inclusions (Fig. 2h, Table S3). These results implicate arginine methyltransferases to c9ALS/FTD pathogenesis.

In summary, we performed a targeted genetic modifier screen in Drosophila and confirm results obtained in two yeast screens11. Both studies consolidate DPRs as major contributing factors to c9 toxicity and point at a role for nucleocytoplasmic transport in this toxicity. Strikingly, the homologs of the strongest genes from the yeast screens were potent modifiers of DPR toxicity in Drosophila. Not only does this validate the effectiveness of modifier genes discovered in yeast in an animal model, it also suggests that DPR pathologies associated with c9ALS/FTD disrupt a highly conserved facet of cell biology.

Depletion of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) such as TDP-43, FUS and others from the nucleus and cytoplasmic accumulation are pathognomonic features of both ALS and FTD17, including c9ALS/FTD18,19,20. The upstream triggers of this nuclear depletion and subsequent cytoplasmic aggregation are unresolved. Our results help to explain how disturbances in nucleocytoplasmic trafficking caused by C9orf72 repeat expansion pathology could trigger RBP mislocalization and subsequent aggregation. Most RBPs are tightly regulated in their cellular localization and shuttle in a strictly controlled manner between nucleus and cytoplasm. Impairments, even subtle, to the nuclear pore, karyopherins, or the Ran-GTP gradient, could perturb this sensitive equilibrium providing a first hit that would eventually lead to aberrant accumulation of RBPs in the cytoplasm, setting off a cascade of aggregation and sequestration of these proteins into pathological inclusions. Interestingly, preliminary histopathological studies suggest that C9orf72 DPR accumulation predates TDP-43 pathology in FTLD patients harboring C9orf72 mutations21,22.

DPR pathology is one way that C9orf72 mutations might contribute to disease pathogenesis. First of all, a role for C9orf72 loss of function, owing to decreased expression of C9orf72, has not been conclusively ruled in or out. A recent report potentially even links the C9ORF72 protein to nuclear transport23. Secondly, sense and antisense RNA transcripts produced from the GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat expansion accumulate in the nucleus and cytoplasm of mutation carriers3 and could cause disease by an RNA toxicity mechanism (e.g., by sequestering important regulatory proteins like splicing factors and other RNA-binding proteins). Two recent studies report the results from genetic screens similar to ours using GGGGCC repeat fly models24,25. Compellingly, these studies also identify nuclear transport as a key pathogenic factor in these fly models, hereby suggesting that the repeat RNA itself could also directly perturb nuclear transport. However, two other reports have ruled out RNA toxicity in flies, at least at the short lengths used in the current models and attribute all observed phenotypes to DPR toxicity10,26. Moreover, since we identify similar modifiers using a pure DPR model, this raises the question whether the repeat RNA itself is truly involved in the observed nuclear transport defects.

The three potential pathogenic mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and future studies will be required to disentangle the relative contributions of DPR proteotoxicity, RNA toxicity and C9orf72 loss of function to c9FTD/ALS. Moreover, why the same C9orf72 mutations cause dementia in some patients, ALS in others patients and ALS/FTD in yet others, even within the same family, is unresolved and might be influenced by modifier genes. A better understanding of the mechanisms by which C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeats cause disease will allow the identification of novel targets for therapeutic intervention.

Material & Methods

Plasmids and strains

FLAG-tagged DPR expression constructs were designed by manually codon-optimizing the sequence and using Mfold software27 to control for any persistent stable secondary structures (Fig. S6, Table S5). DNA constructs were synthesized by Genscript (Piscataway, USA). DPR constructs were subcloned in CMV6 entry plasmids (Origene) for expression in mammalian cells. Subcloning to the pUAST-attB backbone allowed the generation of transgenic fly lines by targeted insertion into the 62E1 attP locus on the third chromosome (GenetiVision, USA). The PRMT1-EGFP construct was a kind gift of Dr. F. Fackelmayer (Laboratory for Epigenetics and Chromosome Biology, Ioannina, Greece).

Lifespan assay

Lifespan experiments were performed using, the TARGET system28. The tub-Gal4 or the D42-Gal4 driver was combined with a ubiquitously expressed temperature-sensitive Gal80 inhibitor (tub-Gal80ts). Fly crosses were grown at 18 °C and adult progeny of carrying the tub-Gal4 or the D42-Gal4 and tub-Gal80 chromosomes and the UAS-DPR responder gene were shifted to 29 °C to allow expression of the transgenes. Females were collected within 24 hr of eclosion and grouped into batches of 10 flies per food vial. Fresh food vials were provided every 2–3 days.

Dot blot analysis

The GMR PR25 screening stock was crossed with the four suppressor lines and offspring was collected. 30 flies per condition were decapitated and fly heads were homogenized in 30 μl of RIPA buffer. 15 μl of homogenate was spotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham) and air dried. Loading controls were visualized using Coomassie staining (Life Technologies). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk powder (Bio-Rad) in TBS-T buffer and probed with a custom rabbit PR antibody (Thermo Scientific). HRP-labeled anti rabit secondary antibody was used (Dako) and membranes were imaged using chemiluminescence (Pierce) and an Image Quant Las 4000 imaging station (GE).

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells (ATCC) were cultured in high glucose DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Greiner), 4 mM Glutamax (Invitrogen), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL) and non-essencial amino acids (1%). Neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y cells, ATCC) were cultured in high glucose DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Greiner), 4 mM Glutamax (Invitrogen), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL) and non-essencial amino acids (1%). Cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 7% CO2. Cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry and microscopy

Fly brains were dissected and fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. Cells were fixed 24 h after transfection in 4% formaldehyde in PBS and stained according standard protocols. Following antibodies were used: anti-FLAG (F3165, Sigma), rabbit anti-FLAG (#2368S, Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-PR (custom generated antibody, Thermo Scientific), ASYM24 (07-414, Millipore), rat anti-Elav (7E8A10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). AlexaFluor 555 and AlexaFluor 488 secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) were used. Nuclei were visualized using Hoechst counterstaining (Sigma). Slides were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Life Technologies).

The ASYM24 antibody was originally generated against an interrupted GR repeat (KGRGRGRGRGPPPPPRGRGRGRG). This antigen shows strong sequence similarity with GR and hence was able to detect GR methylation, but not PR methylation. The antibody was specific for methylated residues as staining was abolished using a general methylation inhibitor Adox.

Confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta NLO confocal microscope and SIM microscopy was performed using a Zeiss Elyra S.1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). SIM calculations were performed using default settings. Images were analyzed, formatted and quantified with FIJI and ImageJ software. For all experiments representative photographs are shown from multiple wells from transfections with at least two cell passages, or from multiple fly brains.

Autopsied brains of six C9orf72 carriers and two non-disease controls were obtained using informed consents and protocols that were approved by the Ethical Committee of University of Antwerp and Antwerp University Hospital and stored in the Antwerp Biobank of the Institute Born-Bunge. Methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Clinical data are shown in Table S6. After a fixation period of 8 to 16 weeks in 10% buffered formalin, 5 μm slices were cut from following regions: frontal cortex, hippocampus with dentate gyrus and parahippocampal gyrus, cerebellar cortex, medulla oblongata. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and pretreated with citric acid 0.1 M. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed with anti-hnRNPA3 antibody (AV41195, Sigma) and ASYM24 antibody (07-414, Millipore). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and images were taken on an Axioskop 50 light microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a CCD UC30 camera (Olympus Inc.).

RNAi modifier screen

To identify modifiers of our PR25 eye phenotype we crossed 121 RNAi lines with our screening stock. The RNAi lines were obtained from VDRC or Bloomington Drosophila stock center (USA). For each cross the collected offspring was divided by sex and the genotypes were counted according to the balancers. The offspring ratio was determined by (expected offspring/counted offspring). For each sex we subsequently assigned an average color using following scoring scale (white = 1, yellow = 2, yellow-orange = 3, orange-yellow = 4, orange = 5, orange-red = 6, red-orange = 7, red = 8). Afterwards, each fly was individually scored for the presence of necrotic spots using following scoring scale (not affected = 0, mild = 1, medium = 2, heavy = 3, extreme = 4). We crossed each line at least two independent times. After compiling all data, two researchers assigned independently a status to each RNAi line (no effect, enhancer or suppressor) as compared to a cross of the screening stock to the RNAi w1118 background. Only whenever a gene was represented by at least two RNAi lines showing a similar effect on the phenotype, the gene was classified as an enhancer or suppressor. When shown, statistics were carried out using Prism software.

RNAi lines did not present with a degenerative eye phenotype by themselves. Two RNAi lines used had a ‘greasy’ eye phenotype reminiscent of mitochondrial eye phenotypes. These lines indeed had reported off target effects on genes involved in eye development: i.e. v105181 off target CG8085, v36103 off target CG4389. Importantly, both these hits were verified by independent RNAi lines without this ‘greasy’ eye phenotype.

Structural modeling

We employed the FoldX force field29 to model PR and GR in the binding pocket of transportin-1 (PDB code: 2OT8). In addition, we performed an unrestrained energy minimization using the YASARA2 force field to optimize the interactions between the PR/GR peptide and the binding pocket of transportin 130. The graphical representation was generated using the Yasara program (version 13.2.21) where negatively charged residues in the binding pocket, within a distance of 5 Angstrom of the peptide, were colored in blue.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Boeynaems, S. et al. Drosophila screen connects nuclear transport genes to DPR pathology in c9ALS/FTD. Sci. Rep. 6, 20877; doi: 10.1038/srep20877 (2016).

References

Renton, A. E. et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257–268 (2011).

DeJesus-Hernandez, M. et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256 (2011).

Ling, S. C., Polymenidou, M. & Cleveland, D. W. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron 79, 416–438 (2013).

Mori, K. et al. The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science 339, 1335–1338 (2013).

Zu, T. et al. RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, E4968–4977 (2013).

Ash, P. E. et al. Unconventional translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion generates insoluble polypeptides specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 77, 639–646 (2013).

Kwon, I. et al. Poly-dipeptides encoded by the C9orf72 repeats bind nucleoli, impede RNA biogenesis and kill cells. Science 345, 1139–1145 (2014).

Mizielinska, S. et al. C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science 345, 1192–1194 (2014).

Wen, X. et al. Antisense Proline-Arginine RAN Dipeptides Linked to C9ORF72-ALS/FTD Form Toxic Nuclear Aggregates that Initiate In Vitro and In Vivo Neuronal Death. Neuron 84, 1213–1225 (2014).

Tran, H. et al. Differential Toxicity of Nuclear RNA Foci versus Dipeptide Repeat Proteins in a Drosophila Model of C9ORF72 FTD/ALS. Neuron 87, 1207–1214 (2015).

Jovicic, A. et al. Modifiers of C9orf72 dipeptide repeat toxicity connect nucleocytoplasmic transport defects to FTD/ALS. Nat Neurosci 18, 1226–+ (2015).

Floch, A. G., Palancade, B. & Doye, V. Fifty years of nuclear pores and nucleocytoplasmic transport studies: multiple tools revealing complex rules. Methods in cell biology 122, 1–40 (2014).

Dormann, D. et al. Arginine methylation next to the PY-NLS modulates Transportin binding and nuclear import of FUS. The EMBO journal 31, 4258–4275 (2012).

Neumann, M. et al. Transportin 1 accumulates specifically with FET proteins but no other transportin cargos in FTLD-FUS and is absent in FUS inclusions in ALS with FUS mutations. Acta Neuropathologica 124, 705–716 (2012).

Dormann, D. et al. ALS-associated fused in sarcoma (FUS) mutations disrupt Transportin-mediated nuclear import. The EMBO journal 29, 2841–2857 (2010).

Scaramuzzino, C. et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 and 8 interact with FUS to modify its sub-cellular distribution and toxicity in vitro and in vivo. PloS one 8, e61576, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061576 (2013).

Neumann, M. et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133 (2006).

Mackenzie, I. R. et al. Dipeptide repeat protein pathology in C9ORF72 mutation cases: clinico-pathological correlations. Acta neuropathologica 126, 859–879 (2013).

Mann, D. M. et al. Dipeptide repeat proteins are present in the p62 positive inclusions in patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neurone disease associated with expansions in C9ORF72. Acta Neuropathol Commun 1, 68, doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-68 (2013).

Keller, B. A. et al. Co-aggregation of RNA binding proteins in ALS spinal motor neurons: evidence of a common pathogenic mechanism. Acta Neuropathologica 124, 733–747 (2012).

Baborie, A. et al. Accumulation of dipeptide repeat proteins predates that of TDP-43 in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration associated with hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9ORF72 gene. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41(5), 601–12, doi: 10.1111/nan.12178 (2014).

Proudfoot, M. et al. Early dipeptide repeat pathology in a frontotemporal dementia kindred with C9ORF72 mutation and intellectual disability. Acta neuropathologica 127, 451–458 (2014).

Xiao, S. et al. Isoform-specific antibodies reveal distinct subcellular localizations of C9orf72 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 78, 568–583 (2015).

Freibaum, B. D. et al. GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9orf72 compromises nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 525, 129–+ (2015).

Zhang, K. et al. The C9orf72 repeat expansion disrupts nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 525, 56–+ (2015).

Mizielinska, S. et al. C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science 345, 1192–1194 (2014).

Zuker, M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Research 31, 3406–3415 (2003).

McGuire, S. E., Le, P. T., Osborn, A. J., Matsumoto, K. & Davis, R. L. Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science 302, 1765–1768 (2003).

Schymkowitz, J. W. et al. Prediction of water and metal binding sites and their affinities by using the Fold-X force field. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 10147–10152 (2005).

Krieger, E., Koraimann, G. & Vriend, G. Increasing the precision of comparative models with YASARA NOVA - a self-parameterizing force field. Proteins-Structure Function and Genetics 47, 393–402 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. F. Fackelmayer for his kind gift of the PRMT1 plasmid. S.B. acknowledges A.v.d.W. for proofreading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions. Research was funded by the KU Leuven, VIB, the European Research Council in the context of the European’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013 and ERC grant agreement n° 340429), the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) G.0983.14N, the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Programme P7/16 initiated by the Belgian Science Policy Office, the Association Belge contre les Maladies Neuro-Musculaires (ABMM), the ALS Liga (Belgium) and the ‘Opening the Future’ Fund. W.R. is supported through the E. von Behring Chair for Neuromuscular and Neurodegenerative Disorders and the “Hart voor ALS” Fund, KU Leuven. K.J.V acknowledges funding from an ERC Starting Grant 241426, HFSP program grant RGP0050/2013, KU Leuven NATAR Program Financing, VIB, EMBO YIP program, FWO and IWT. P.C. is supported by funding from VIB, FWO and IWT. The Antwerp site acknowledges funding by the Belgian Science Policy Office Interuniversity Poles Program P7/16; the Medical Foundation Queen Elisabeth (QEMF); the Flemish government initiated Methusalem excellence program; the Flemish government initiated Flanders Impulse Program on Networks for Dementia Research (VIND); the Alzheimer Research Foundation (SAO-FRA); the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO); the Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology Flanders (IWT) and the University of Antwerp Research Fund; Belgium. A.D.G. is supported by the Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins, Target ALS and NIH grants 1R01NS065317 and 1R01NS073660. S.B. and J.S. received a PhD fellowship from the Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology (IWT). E.B. and I.G. hold a post-doctoral fellowship, A.S. holds a PhD fellowship and P.V.D. a senior clinical investigatorship from FWO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., E.B., E.M., I.G., A.S. and G.D.B. planned and performed the experiments. W.S., J.S. and I.C. provided technical support. I.G., A.S., I.C., M.C. and C.V.B. provided human samples and performed immunological stainings. G.D.B., F.R. and J.S. performed in silico docking studies. K.J.V., P.C., P.V.D., W.R., A.J. and A.D.G. provided ideas for the project and participated in writing the paper. L.V.D.B. planned and supervised the experiments. S.B., E.B., A.D.G. and L.V.D.B. wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Boeynaems, S., Bogaert, E., Michiels, E. et al. Drosophila screen connects nuclear transport genes to DPR pathology in c9ALS/FTD. Sci Rep 6, 20877 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20877

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20877

This article is cited by

-

Nuclear-import receptors as gatekeepers of pathological phase transitions in ALS/FTD

Molecular Neurodegeneration (2024)

-

Artificial microRNA suppresses C9ORF72 variants and decreases toxic dipeptide repeat proteins in vivo

Gene Therapy (2024)

-

Repeat length of C9orf72-associated glycine–alanine polypeptides affects their toxicity

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2023)

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a neurodegenerative disorder poised for successful therapeutic translation

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2023)

-

Nuclear pore complexes — a doorway to neural injury in neurodegeneration

Nature Reviews Neurology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.